Complete Guide: How to Raise, Butcher, and Process Chickens

This post may contain affiliate links, please see our privacy policy for more information.

Updated: August 10, 2024

The time has come to butcher and process another set of chickens on our farm. This is always a complicated matter, one that we do not necessarily enjoy doing, but one that we know is necessary for our beliefs and lifestyle choices. We have been raising our own meat and processing it ourselves for four years now, and we have been actively only been purchasing locally raised meats for nearly a decade now. It is something that we realized was better for our bodies and the sustainability of our planet and community. Locally raised meat that has been raised on pasture has an incredibly higher quality and superior flavor over factory farmed meats, aside from being an absolutely better quality life for the animal.

In this guide, I share how to raise chickens for meat, humanely butcher chickens, and process a meat chicken for storage for up to one year. **If you are squeamish about meat processing photos, you have been warned!

why we raise our own meat:

Our minds changed about meat back in 2014 and 2015 after watching several documentaries and researching about industrial and conventional farming and slaughtering processes. While we fully understand that this is not always a feasible option for everyone, and that small farming most likely won’t become a part of every person’s life and change the way the world eats, we know that this is a small way that we can actively make a change.

We also hope that this helps to open the eyes of others. While viewing and learning about the butchering process can be triggering for some, I do honestly believe that if you eat meat or have ever eaten meat, this is something that you need to see and understand! All meat that humans eat once had a face, a heartbeat, and a personality. It did not just appear at the grocery store. Personally, I would rather know about the life of that animal and its slaughter than not know anything about it, and that justifies this lifestyle enough for me.

is it safe to butcher your own meat?

As we enter our fourth year of animal butchering, I feel the most at peace with the process than I have felt in the past. There are several sides to this story. One being the loss of the mindset that this is dangerous for our health. I have a complicated relationship with the information and regulations provided by the USDA and FDA when it comes to processing homegrown meat and other foods. Their guidelines are in place to prevent illness, food poisoning, and food contamination. There is also plenty of information that leads me to believe that there are too many hands in the commercial food industry’s pot, and those hands like to scare us into believing that factory farmed food is the only type of food that’s safe for us to consume, and we can see that isn’t necessarily true. Food recalls continue to happen more frequently, and we are becoming more aware that the added ingredients in processed meats are making us terminally ill.

As someone who grew up in a city setting, if I was looking at my own blog right now with no prior knowledge of an off-grid lifestyle I would have a hard time believing myself. Isn’t it unsanitary? Aren’t you going to get salmonella?

The short answer is: it’s highly unlikely. Understanding basic food sanitary practices is enough to understand how to butcher and process a chicken. This is something that you can easily learn online, in books, or take a food and kitchen safety class online or in-person. All restaurant and food establishments (including me) have to take this class, and it’s incredibly helpful things to know!

You can do this, too. It just takes a lot of research and a little bit of courage.

how we raise our chickens:

Our chickens are purchased as day-old chicks from Hoover’s Hatchery in Rudd, Iowa. This is a short trip for them, as we are located in Iowa as well. They arrive in the mail, and this hatchery has a rule of 15 chicks minimum per shipment. Because we are a moderately sized family of seven on a small farm of 3.5 acres, we only order 15 to 20 chicks at a time, once in the summer and once in the fall. That will leave us with around 30 to 40 chickens until next spring.

the best chicken breeds for meat production:

The breed of chicken that we raise specifically for meat production are Cornish Cross hens. This is hybridized breed which was bred specifically for its large breast meat. These hens gain weight excessively fast, reaching their mature weight of 6 to 8 lbs (2.7 to 3.6 kg) by 6 weeks old. For other chickens, they are not at their mature weight until 26 to 30 weeks old. Cornish Cross chickens are docile, lazy, and can easily develop heart conditions from being obese. They grow so quickly that they outgrow their feathers, leaving them pink and naked looking. This is not due to being overcrowded.

We chose this breed because of the short timeline and the amount of meat from the bird. That means that we can process two rounds, one in summer and one in fall, before it gets too cold outside for pasturing the birds.

There are several other Dual Purpose Chickens that work for meat production such as Barred Rock, Black Australorp, Black Jersey Giant, Buff Orpington, Delaware, New Hampshire, Brahma, and Rhode Island Red to name a few.

caring for cornish cross chickens:

Shelter:

We have raised our Cornish Cross chickens with a few different methods. I do have a preferred method, but they all work just fine.

Chicken Coop/Enclosed Run: My preferred method for raising Cornish Cross chickens is by placing them into a traditional chicken coop and enclosed run with access to open grass. This is the way we also raise our laying hens. It provides them with a place to shelter and stay safe from predators as well as provides shade, or we keep them locked up on days when we need to be away from the farm. We can easily open the door and let them out to walk in the grass and get some much needed exercise. It prevents the build up of manure and keeps down the smell - Cornish Cross are smelly!

Chicken Tractor: Another option is using a chicken tractor, which is smaller enclosure that is open to the air but is moved once or twice daily around the farm so that the chickens are on fresh grass. Chicken tractors are generally DIY operations, usually a simple frame covered in hardware cloth to protect from predators.

In a nutshell, here is what you will need to provide as a shelter for Cornish Cross chickens:

Roughly about 2 square feet (0.19 sq m) per chicken at minimum. They do grow quickly and get quite large, so plan to move them more often if you have less space.

A coop and a run: a place to shelter from the sun and predators, and an open space to roam:

FEED:

Cornish Cross chickens can be raised on a chick starter/grower feed from the day they are brought home until the day they are butchered. A Cornish Cross will eat an average of about 2 lbs (0.9 kg) of feed per day, though this will vary depending on how active your birds are.

Cornish Cross chickens will, quite literally, sit at the feeder all day long and eat if you let them. To help prevent this, their food and water need to be moved at least once per day if not multiple times per day. This physically forces them to get up and move to find food. It can also be helpful to restrict food intake so that they do not over-indulge, which can lead to health-related issues and death. I would not restrict their food intake to less than 0.25 lb (0.11 kg) of feed per day.

Scheduling the feedings for this particular breed is necessary. It is recommended to feed them for 12 hours, and take the feed away for 12 hours. This can easily done by placing the feed out in the morning and taking it away at dusk. They should have access to ample amounts of clean water, which they will go through more of than laying hens. A poultry waterer with a twist base and tray is my preferred waterer for this breed as they tend to make the water mucky, and this will help to keep it cleaner for longer!

BEFORE culling Your Chickens:

Before culling the chickens, be sure to restrict their food intake for at least 12 hours and no more than 24 hours. Remember, this is the one worst day of their entire lives. Killing a chicken with a crop, stomach, and intestine full of food is not fun. I have done this, and it can be a mess if you make the wrong cuts!

Do not let Cornish Cross chickens live past 10 weeks of age, or they run the risk of having severe health problems. I prefer to cull my Cornish Cross between 7 and 9 weeks of age, for an average 3 to 5 lb (1.3 to 2.3 kg) chicken.

preparation and tools for butchering:

To butcher, you will need to prepare some tools and equipment.

BLEACH. I do not normally use bleach very often in our home as I prefer more natural disinfecting products. However, for the sake of being extremely sanitary, especially since we butcher outdoors (which is a GREAT place to do this for open air circulation), I do use bleach for sanitizing surfaces and tools as we work.

EASILY CLEANABLE SURFACES. You will have to process your birds somewhere. I prefer to use a stainless steel prep table as it easy to clean and disinfect.

WASH BUCKET/SINK/WATER. If you are doing this inside, have a wash bucket with diluted beach on hand. For us, we have a hose nearby to spray off the surface and disinfect with bleach and paper towels. While I love primitive tools, it is better to be as sanitary as possible.

CULLING CONE. We use a culling cone to slaughter our birds. This is incredibly helpful to have as it prevents them from bruising and breaking their wings/legs.

STAINLESS STEEL TUBS & BUCKETS. There will be a lot of mess. Some are things that you may want to save like blood, feathers, and internal organs. Have stainless steel buckets set aside for collecting these things.

30 QUART STOCK POT. To remove the feathers, you must dunk the entire chicken into a pot of boiling water. I like using a 30 quart stock pot best.

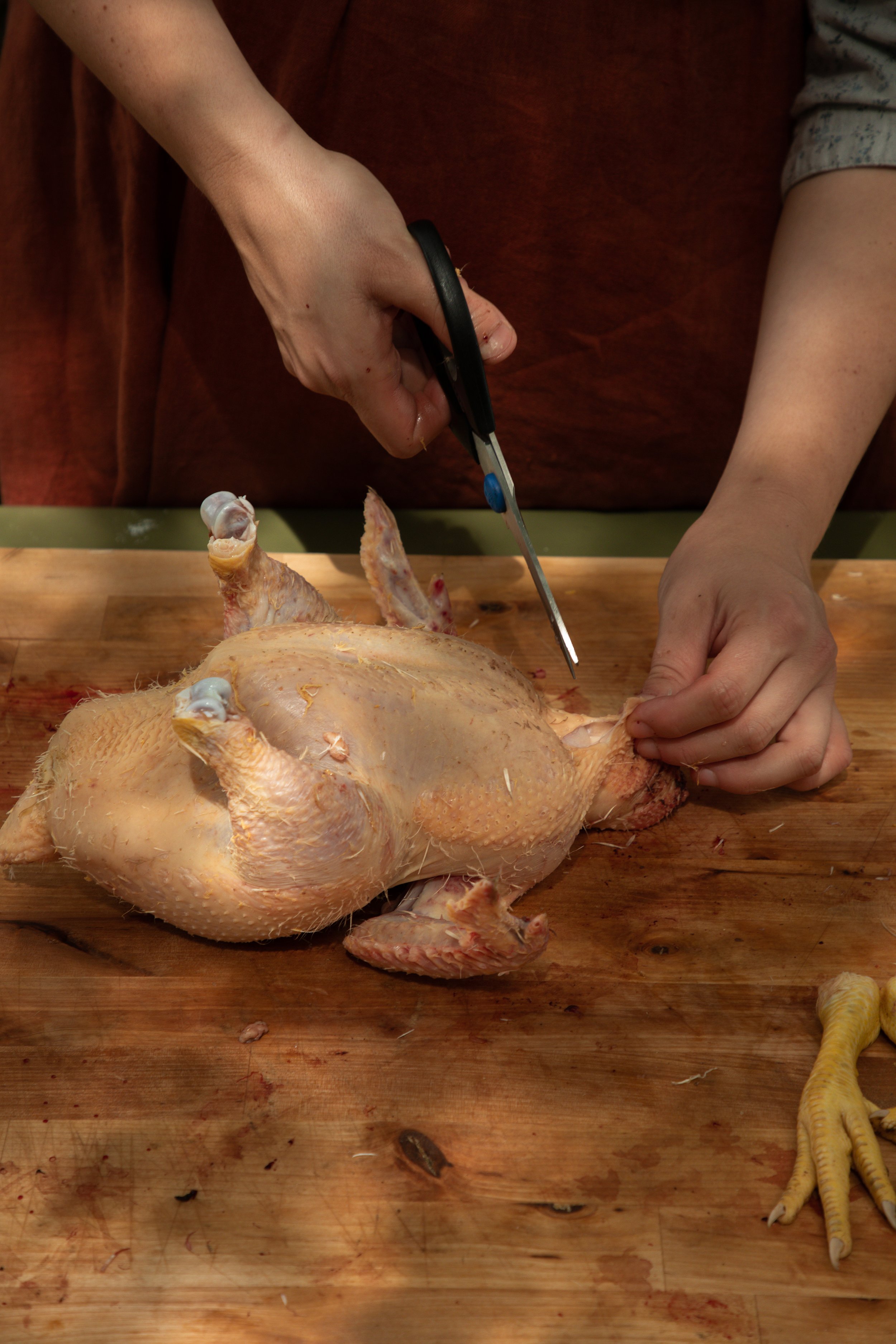

BUTCHERING KNIVES. Butchering knives can be helpful as they are shaped specially for dealing with cutting around bone and through joints. You will need sharp knives of any kind for the slaughtering and evisceration. I love to use kitchen scissors for butchering, too.

COOLER WITH ICE. It is best practice to get the chickens as cold as possible after butchering is finished. We do not have access to a commercial flash freezer, so an ice bath is the next best thing. As we butcher, we store the finished chicken carcasses in a cooler packed with ice and cold, clean water. They are dunked into the water immediately after being finished and stored in the cooler as we work. Make sure the cooler is sanitized before using.

FOOD SEALER OR FREEZER BAGS. Once the chicken is finished, we use a vacuum Food Sealer to package the birds and freeze them. 2 Gallon freezer bags work best for chickens that are about 3 to 5 lbs.

how to slaughter chickens:

There is no FDA or USDA approved “humane” way to kill a chicken, at least in terms of slaughtering at an approved slaughter house. The most humane way to kill a chicken is debated. It is my belief that the least traumatic way to cull a chicken is to stun the animal and then kill in the least painful and quickest way possible. Some people gas chickens in a chamber or use a gun. I do not think either of these options are feasible for small homestead butchering, and is really quite traumatic.

The best methods are slicing the carotid arteries in the neck, decapitation, or breaking the neck. We prefer slicing the carotid artery, as it is the easiest way for us. Here is the step-by-step processing of culling a chicken this way:

Prepare the Culling Area. Drill the culling cone into the side of a tree or wooden post. Place a stainless steel bucket underneath the culling cone to collect any dripping blood. Have a pot of water boiling ready to go, the butchering station cleaned and ready for evisceration, and a cooler filled with ice and water for storing the finished chicken.

Stun the Chicken. Hold the chicken around the entire body with the wings pressed to its sides. With a swirling motion, move the chicken around in a circular motion in front of you. This disorients them and makes them dizzy, which makes it easier to get them into the culling cone.

Put the Chicken in the Culling Cone. Once disoriented, flip the chicken upside down and place the head into the culling cone. The cone prevents their wings from flapping as they bleed out, which can result in broken wings and bruising.

Cut the Artery. With an sharpened knife, make a ventral neck cut, or horizontal cut across the entire neck just below the jaw bone. This type of cut bleeds out the chicken rapidly, and is beneficial for the welfare of the bird as well as the quality of the meat. Once cut, check to see if there are two jets of blood streaming in an upside-down V-shape. This indicates that both carotid arteries have been severed. If the blood is slow-flowing, the cut was not made deep enough.

Bleed Out the Bird. Once the artery is cut, the chicken’s body will go into shock and begin to involuntarily jerk and wiggle. This is normal, though difficult to witness. Wait for the bird to bleed out for at least 3 minutes, checking for any signs of life such as corneal reflex or rhythmic breathing. Make sure that the chicken is confirmed dead before continuing the process. If they were not cut deeply enough, it can be a good idea to decapitate the chicken.

Clean the Carcass and Cone. It’s fairly common for the chicken to defecate during its death, so you will want to have a hose and some diluted bleach on hand to spray down the chicken and culling cone before the next bird.

de-feathering the chicken:

While I have killed a handful of chickens and even a hog, I tend to be the person that butchers the chickens. The next step is to remove the feathers from the chicken.

Prepare the Work Area. As stated above, have the stock pot with boiling water ready to go at a consistent rolling boil. We have used a propane burner stand in the past as well as wood fire. I prefer to work over the wood fire, but that’s just my personal preference.

Dunk the Chicken. Holding the chicken by its feet, dunk the bird all the way up to the first joint in the legs, where the feathers end. You do not have to dunk the scaly feet. Dunk for 1 to 2 seconds then pull it out of the water completely. Repeat the dunking for another 1 to 2 seconds and let the water drip fully away from the chicken. Be careful not to drop them into the water - they can be heavy!

Pluck the Feathers. Move the wet chicken to a sanitized spot that is separate from where you will eviscerate the chicken. Begin pulling out the feathers with your fingers. Dunking the chicken in hot water opens up the pores to allow for easier removal of the feathers, which is harder to do with game foul such as ducks and turkeys. It is easiest to pull them out by pulling them in the opposite direction from which they grow. This job can be tedious, though you will begin to get faster at it.

Do Your Best. The hardest feathers to remove are the wing tips, the tail, and around the vent (rectum). Try your best to remove all the small down feathers until the chicken is naked. It is okay if they are not all fully removed. This is hard to do in the moment, especially when there are other chickens waiting to be processed. Just do your best and work at a steady pace, if possible! You can always remove any little feather that you missed later before cooking.

eviscerating the chicken:

The next step is to eviscerate the chicken, or to remove the internal organs and turn it into an edible product, similar to what you would purchase at the grocery store or butcher. This is the most difficult part, aside from getting through the act of culling the chicken.

This is also where things can go wrong, namely contaminating the meat with the chickens’ feces while trying to remove the intestines. It can be a scary undertaking, but just remember that humans have been doing this for thousands of years. You can, too!

Part One: remove the feet

Cut the Foot Joint. The first cut is to remove the feet. Feel around with your fingers for the place where the joint of the foot and leg meet. With a sharp knife, slice in between the joints of the leg and foot. This should be one simple cut without touching bone that removes the entire foot.

Keep the Feet. The feet are entirely edible and should be kept! Remove the toes and thoroughly wash them after the culling process is finished. They can be made into a gelatinous broth.

Part Two: remove trachea, esophagus, crop, and neck

Remove the Neck. Make a small cut into the skin of the throat until you can see the muscles of the neck. Pull this skin up and over the top of the neck, so that it falls to the back of the chicken.

Locate the Trachea, Esophagus, and Crop. With the neck muscle now exposed, locate the trachea (wind pipe; it is ribbed) and the esophagus. You will find that the esophagus is connected to a large sack on the chicken’s right side breast, underneath the skin. This sack is called the crop, which is where the chicken’s food first goes before entering the digestive tract. The crop grinds up the feed for them to be more easily digestible. If you restricted the food intake of the chickens before butchering, this will mostly likely be empty. If not, it may be full of food, grass, rocks, and acid to break down the food. It may even smell like yeast.

If the Crop is Full: Be careful to not break the sack or else you will spread all of the food contents over the meat. If this does happen, use a hose or sprayer to wash this away as soon as possible.

Remove the Neck Parts. Carefully pull the crop away, removing the thin membrane attaching it to the breast meat. Once the crop is detached, pull or cut away the trachea and esophagus as far down the neck and into the chicken’s chest as possible. Discard these parts for scrap. If there is excess neck skin still attached, you can cut this off as well and discard it.

Remove the Neck (optional). You may choose to leave the neck or remove it. This is simply done by cutting as far down the neck as you prefer and slicing in between the vertebrae. You can also rip it off, if that is easier. You may choose to save the neck, so place it in a bucket of parts to save for later.

Part Three: remove internal organs:

This is the scariest part, but you can do it!

Remove the Tail. Begin by making a small cut through the vertebrae of the spine above the tail and oil gland. Slice through the spine until you feel the vertebrae separate. Be extremely careful to slice slowly and gently to avoid cutting through the intestines.

Locate the Intestines. Once cut, you will be able to see the intestines along with some connective tissue. Gently cut down the sides of the tail and vent (rectum) from the initial cut you made, inside of the pelvic bones, to create some space.

Cut Around the Vent (Rectum). At this point, I flip the chicken over onto its back with the breast facing up. Make a cut just under the bones of the ribcage, cutting through until you can see the internal organs. Be careful not to cut into them. This is easiest to do with kitchen scissors. Slice down the sides of the ribcage and try to meet up with the cuts that you made along the sides of the tail and vent to fully expose the bottom half of the chicken. It will look like a gaping hole, and the internal organs will begin to spill out a bit.

Make Sure Everything is Still Attached. When these cuts are met, the vent (butt hole/rectum) should still be attached to the large intestine. You should be able to see where that connection is and move it away from the body. This is going to take some experience to learn, but it is best to go slow and familiarize yourself with the anatomy so that you do not accidentally cut through the intestines. Even with food restriction, the intestines are still usually filled with feces and it will leak out if sliced into, and it will contaminate the meat. You will know if you accidentally cut into the intestine because it reeks terribly… I know from experience. If this does happen, remove the intestines quickly and efficiently and wash the chicken with clean water immediately.

Remove the Internal Organs & Vent. With your hand, fully reach inside the cavity of the chicken and pull out the internal organs with your hands. It’s really that simple.

Choose Your Cut. At this point, you can choose to leave your chicken whole or cut the chicken into parts, such as legs, thighs, and breasts.

Put in the Ice Bath. The chicken is now finished and is ready for packaging. If you are processing several chickens, place the finished chicken into an ice bath to chill as soon as possible before moving onto the next bird. This will prevent any contamination and growth of bacteria between birds, and help to get them cold before going into the freezer.

parts of a chicken and what to use them for:

But what do you do with the internal organs? Some of these parts are used for cooking, and others can be used for in the garden or for feeding animals. Here is some insight on the Nose-To-Tail method of butchering an animal:

Head. The chicken’s head can be used for eating, and this is quite common in eastern parts of the world. You can process the head in a similar fashion to the the rest of the body. You can leave it attached to the body, if you want. Dunk it in hot water and remove the feathers on the head. Leave or remove the beak and cook the entire head whole. If you do not want to eat the head, it can be boiled down and the gelatinous broth can be fed to dogs or cats.

Neck. The neck is a yummy piece of the chicken. Because it is mostly made up of bones and cartilage, it’s perfect for flavoring the pan drippings of a roasted chicken, or making broth. You can eat it in any way that you would normally eat any other part of the chicken.

Heart. The chicken heart is incredibly delicious. This organ can be cooked alongside the meat during roasting, over the fire, boiled, etc. It’s quite tasty in a soup or stew, and you don’t really notice that you are eating it if you chop it up first.

Liver. The liver of a chicken is eaten like the liver of any other animal. It is high in iron and tastes wonderful sautéed with onions and garlic in some butter or olive oil and lots of salt and pepper.

Gizzard. The gizzard is where the chicken’s food is finally ground up and turned into fuel for the body or waste. It is round and deep red in color with a white, circular member around it. This needs to be cut into and cleaned out as it is usually filled with food. Then, it can be sauted or fried.

Intestines. The intestines are edible, though you will want to thoroughly wash them before cooking. They are most often served in Asian cuisine and are a popular street food. Personally, I have never eaten the intestines, mainly from lack of confidence. I generally just burn them, or I have washed, boiled, and fed them to the barn cats.

Feet. The feet are amazing! Made up of 70% collagen, they are an incredibly healthful part of the chicken’s body. They can be roasted or fried, but I like to boil them down into bone broth.

Bones. Save the carcass of your chickens! They can be boiled for several hours and turned into liquid gold, otherwise known as bone broth.

storing the chicken:

Seal The Chicken. When the chicken is all finished processing, it’s time to prepare it for long term storage. We have used 2 gallon freezer bags in the past. Now, I prefer a vacuum food sealer. Weigh the chicken with a kitchen scale, then place the chicken in the vacuum food sealer bags and label the date and weight. Get them into the freezer as quickly as possible. Then you are done!

can you sell homegrown meats to the public?

If you are going to do this yourself, you should know that it is illegal to sell processed meat to others without it being inspected by the USDA. Raising and butchering homegrown meat is only a feasible option if it is for your personal use, not for resale.

You can apply for a license to resell meats at a small scale. In the past, we had a successful CSA program (Community Supported Agriculture), where we partnered with a small family licensed production that raised chicken and hogs. If you live in the United States, you need to go through a series of inspections from the USDA and Food Safety Inspection Service. This involves various types of inspections, including whether you plan to sell at the federal or state level, USDA certified organic labeling, and nutritional information.

I do know from experience that it is incredibly difficult to get approved to sell raw domestic raised poultry. They have to be butchered in an approved facility, and there must be an inspector present on the day that the birds are being processed. They also must be flash frozen. This includes a lot of professional equipment and fees.

final thoughts:

Overall, this entire process is, well… a PROCESS. It takes several hours to get through a round of 20 chickens, and we are dead tired by the end of it. The first chicken is always the hardest, and we are countlessly grateful for the life that it gave to feed our family. I have been on both sides of the fence for meat eating. I was vegan for two years and plant based for other times in my life. I honestly believe that if you are going to eat meat, this is the best option for doing so, or finding it from a local farm that is able to have their meat inspected and approved for selling.

If you have any questions about our process, please let me know! I am happy to chat about it with you. I hope that this post eased your mind and helped you to learn more about raising your own meat chickens.

xoxo Kayla